In this blog post I will discuss the fears of humans being controlled by behavioural science. This fear receded as criticisms of behaviourism made the discipline seem less capable of achieving the bombastic claims made by the likes of Skinner and Watson. But behaviourism has advanced well beyond Skinner and Watson and current behavioural science is again looking at ways of controlling rule governed behaviour. After discussing Skinner’s early work on control and counter control I will evaluate contemporary behavioural science and its potential for predicting and controlling verbal behaviour linking behavioural control with the rise of Artificial Intelligence.

In Skinner’s ‘Science and Human Behaviour’ in 1953 he speculated on ways behavioural technology could improve the lives of people if implemented properly. However, there were those who didn’t like the imposition of scientists into human affairs. Some of this opposition was simple fear that science was encroaching on subject matters typically tackled by the humanities. But for others they found the Skinner’s emphasis on “prediction and control” chilling. People feared a future where behavioural scientists would eventually achieve control over ordinary human subjects and shape and control their behaviour at the whim of those in power.

However, as we learned more about animal behaviour, and the factors impinging on such behaviour, the threat from behavioural science began to seem less and less. Breland and Breland’s (1963) work on animal training demonstrated that instinctual drift would mean that non-human animals’ behaviour wasn’t as malleable as earlier naïve behaviourists thought. Skinner, who had long stressed both phylogenetic and ontogenetic factors playing a role in animal behaviour welcomed the work of the Breland’s. On Skinner’s way of thinking it was the behaviourists job to discover the different ways behaviour could be shaped and controlled through different schedules of reinforcement. The behaviourist wasn’t in the game of stipulating how malleable different organisms were. Nonetheless, despite the Breland’s work being congenial to Skinner’s behaviourism, for the public, instinctive drift made the thoughts of behaviourists gaining control over people and shaping their behaviour seem less threatening.

As behavioural scientists continued to study human’s operating under schedules of reinforcement there was more reason to think that humans couldn’t be just shaped at a whim through schedules of reinforcement. Hundreds of behavioural studies on rule governed behaviour[1], have demonstrated that when humans were operating under rules this made them less sensitive to the contingencies of reinforcement. Children below the age of 5 could be shaped under schedules of reinforcement in a similar way to a rat, but once they passed 5 and could follow rules their behaviour became less sensitive to the contingencies of reinforcement (Bentall 1985).

Like the Breland’s work, work on rule-following sprung up in behaviourism (Skinner 1963) and demonstrated that human behaviour was more complex than the behaviour of other organisms. When Sidman (1971) experimentally demonstrated that humans could derive untrained stimulus equivalence, and Hayes (1989) demonstrated that humans could derive untrained relational frames (coordination, comparison, hierarchy, etc). The human under behavioural science began to closer resemble the human as described by cognitive scientists (built with innate constraints, have a species-specific capacity for productive reasoning etc), than it did the human as described by early behaviourists.

With all these facts in place people in the popular press stopped worrying about nefarious behaviourists controlling them. The stuff of nightmares in the popular imagination is now neuroscientists controlling us, or AI controlling us. Fear of behaviourists controlling us is now a part of our quaint past on a par with fears in the nineteen fifties fearing visitors from the Moon.

Nonetheless, Skinner’s point still stands. Our behaviour is controlled by facts in our ontogeny and phylogeny as well as a variety of other factors. Our behaviour is always controlled and science, which gives us the best tools to predict and control phenomenon can help us as a species, gain some degree of control of our collective behaviour. Some of this control is welcome, we are glad that people follow rules that forbid them to enter a stranger’s house without permission or forbid them to drive on the wrong side of the road.

But when it comes to things like Verbal Behaviour people are particularly reticent in ceding control to scientists. Our ability to talk and think about whatever we want is a key component of what it means to be human. Thus, it is the stuff of our nightmares that scientists or politicians gain the ability to control what we can say. Famously, in Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984 the party controlling society, had banned the use of certain words such as ‘Freedom’ and ‘Equality’ etc. With the aim being that to the extent that thought depends on language if you can ban the words from public consciousness people will no longer be able to think the thoughts. Compelling evidence from cognitive science indicates that it is not necessary to have a word in public language in order use a concept (Pinker 1994, 2002). While cognitive science has conclusively shown that our thought is not entirely determined by our language. It is evident that our thought processes are shaped by the type of language we acquire. Lakoff (1987), has demonstrated how the metaphors we adapt will influence the way we think about the world. So, the fear still exists that nefarious scientists in conjunction with political elites will some how conspire to control what we can say perhaps even influencing what we can think. Hence, in recent years there has been an explosion of public intellectuals; usually podcasters who argue that there should be no limits on who can say what. These people call themselves free-speech absolutists.

But as of yet the science of verbal behaviour doesn’t demonstrate any real capacity to control Verbal Behaviour. In fact, as discussed above, once a creature becomes verbal and starts following rules their behaviour becomes less sensitive to the contingencies of reinforcement. Furthermore, as linguists like to note humans appear to have the capacity to construct new sentences which have never been spoken before using their ability to use productive syntax. This type of creativity doesn’t appear to be under the control of any kind environmental or behavioural control.

Nonetheless, we known anecdotally that the type of sentences we use are to some degree shaped because of our history of interaction with particular groups. Skinner tells an anecdotal story about meeting his parents and his lecturers at his graduation. He found the conversation difficult to navigate because he had a history of reinforcement for talking to his family in a particular manner, and a different history of reinforcement for talking in a different manner to his professors. In the conversation he felt the pull of two competing verbal repertoires as he interacted with the two groups of people.

Obviously, however just because Skinner has verbal repertories he used when talking to people in different groups, he was nonetheless capable of creating new sentence to talk about other things which may have interested him or his interlocuters. There is no reason to think that his verbal repertoires were entirely determined by past reinforcement history. Nonetheless, the fact that he felt the pull of two competing verbal repertoires does indicate that the type of speech acts we engage in are to some degree shaped by social contingencies.

Behaviourists have long noted that humans aren’t just passive organisms who submit to control. Humans typically don’t like being controlled and respond to control with two key tactics (1) Aggressive Responses, (2) Moving out of the range of range of controllers or passive resistance (Skinner 1953 p. 193). But in an unequal society with one group being more powerful than another group; aggressive responses may be pointless. Furthermore, with the ability to increase of technology into every aspect of our lives it is more and more difficult to move out of the range of controllers. Humans spend an inordinate amount of time online where they can be reached by a variety of different forces.

As we discussed above when humans begin to develop their language and start following verbal rules this makes them less sensitive the contingencies of reinforcement. Hence, their behaviour when rule governed is more difficult to behaviourally control. Behaviourists have noted that humans engage in a type of rule governed behaviour which is shaped by social consequences. They call this Pliance. There is rule governed behaviour which is controlled by tracking. Where the rules are adopted because they accurately track environmental facts. And augmentative rule following which alters the extent to which rule governed behaviour is reinforcing.

Importantly for our purposes they have started to develop techniques to help them control rule governed behaviour. In a recent paper behaviourists Spencer et al (2022) noted that people had trouble following verbal rules for three reasons: (2) Lack of Credibility of the speaker, (2) Lack of the ability of the speaker or authority figure to mediate contingencies of rule-following, (3) implausibility of a given rule. And they argue that these facts can be overcome through the following techniques. Strengthening augmental control by connecting the rule to what the individual values. Monitoring rule following to assess Pliance rates. Ensuring the contingencies supporting rule following track reality accurately. Deemphasizing freedom threatening language (Spencer et al 2022).

As things stand behavioural techniques employed by psychologists in relation to things like tracking and Pliance typically relate to therapeutic settings. Thus, in therapy a therapist may discuss with a patient how their verbal repertoire is geared toward social compliance sometimes at the expense of tracking reality accurately. But as accuracy in understanding rule following behaviour and how it is controlled increased it may eventually be used by governments to shape how people verbally respond to societal rules. A step in this direction was Stapelton et al 2022 which explored the rule following behaviour of people during the Covid-19 pandemic.

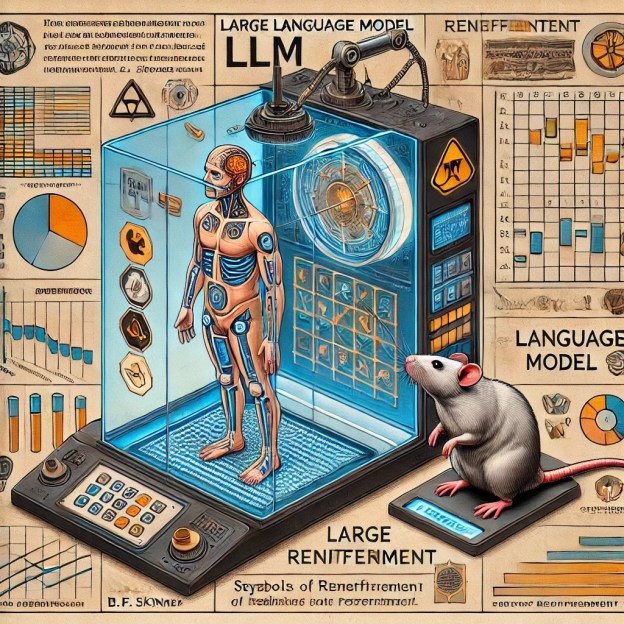

With the creation of Large Language Models which will increasingly appear online it will be possible that most “people” you interact with online will be Large Language Models or other kinds of AI. Large Language Models when being trained can be shaped to reflect the values of the person designing it. Thus, during training using reinforcement the Models will be trained to only answer in ways consistent with the biases of the creators. Children growing up who may be perennially online could end up receiving a massive amount their linguistic data from Large Language Models.

These models sometimes hallucinate answers based on statistical expectations. And other times they will be trained to reflect the values of their designers. It is more and more possible to track what people’s values are based on their online behaviour. What they look at; what they buy, who they interact with. If Large Language Models are linked to attractive avatars and given their impressive manner of being able to answer a surprising number of questions. People may start viewing them as authorities. And this is the first step in them being used as reliable givers of information. Children growing up could end up following the rules of unconscious LLMs whose values were shaped by their creators. This wouldn’t be verbal control of the type Orwell worried about. But it would be a way of shaping the values and verbal repertories of people in ways we may be entirely unaware of.

[1] See for example: Weiner et al (1964), Lippman and Myer (1967), Lowe et al (1983), Hayes et al (1986).