Introduction

In this paper the competence-performance distinction first proposed by Chomsky (1965) will be analysed in relation to behavioural science. The paper will consider three primary criticisms of behaviourism from the point of view of the competence performance distinction: (1) behaviourists decision to stick with describing speech patterns and habits prevent them from constructing a credible theory of performance (Chomsky 1965), (2) Behaviourists methodology of only dealing with performance and eschewing explanations in terms of competence precludes them from being a serious science (Collins 2007), (3) Behaviourists don’t engage in idealisations and are committed to counting every cough in an instance of verbal behaviour and hence reduce their science to triviality (Jackendoff 2002). It will be demonstrated by considering developments in behavioural science that these criticisms are not justified. To illustrate the point, I will discuss explanations in both behavioural psychology (as exemplified by relational frame theory), and behaviourism in philosophy as exemplified by Quine. These examples will illustrate behaviourists appealing to underlying competencies to explain behaviour as well as using idealizations.

The fact that behavioural scientists use idealizations and appeal to competencies, doesn’t tell us much about the truth of their overall theories. But for interdisciplinary interaction between behaviourists and cognitivists to be fruitful; it is necessary that they understand each other positions. To that end it is imperative that the behaviourist position in the competence-performance distinction is explicated in detail.

Chomsky on the Competence and Performance Distinction

Sixty years ago, in his ‘Aspects of a Theory of Syntax’, Chomsky first explicitly made his distinction between competence and performance. In Aspects he is clear that he is not arguing against the study of performance as a field. Rather he is claiming that if one wants to study performance, then one will need to do so armed with an understanding of underlying competence mechanisms (Chomsky 1965 p.10). When discussing competence and performance Chomsky makes a distinction between acceptability judgements made by subjects and the actual grammaticalness of sentences. He argues that acceptability judgements are performance data which can be explained by underlying competence mechanisms (Ibid p. 11).

He goes on to state that the following factors lead to unacceptability judgements; Repeated nesting, self-embedding, nesting of a long and complex element etc (Ibid p. 13). And he explains the unacceptability of, for example, repeated nesting, in terms of the finiteness of our memory (Ibid p. 14). Chomsky notes that people have been critical of generative grammar because of its focus on competence and lack of interest in performance. But he claims that the only research into performance that has had any theoretical interest, has been research that has been led by insights from underlying competence systems (Ibid p. 15). He went on to criticize descriptivist and classification philosophies as standing in the way of developing an adequate theory of performance:

“It is the descriptivist limitation-in-principle to classification and organization of data, to “extracting patterns” from a corpus of observed speech, to describing “speech habits” or “habit structures,” insofar as these may exist, etc., that precludes the development of a theory of actual performance.” (Ibid p. 15)

Chomsky doesn’t specify which theorists argue in this methodologically errant manner; but it will be demonstrated that his criticisms don’t apply to behaviourists in either psychology or philosophy.

Competence and Performance and Behaviourism

In this section I will look at the competence/performance issue from the point of view of behavioural science. I will argue that contemporary behavioural science cannot be described in terms of looking for “habit structures” or extracting patterns from the classification or organisation of data. Rather, behavioural science is discovering facts about the emergence of linguistic usage in the context of tightly controlled experimental settings. These discoveries in behavioural science such as (1) Rule-Governed Behaviour’s interaction with the contingencies of reinforcement, (2) the emergence of stimulus equivalence, (3) The emergence of relational frames, are experimentally controlled emergent properties of linguistic behaviour. Their discovery goes beyond mere “description” or “extracting of data from patterns”. Furthermore, there is no reason to think that such emergent species-specific performance data is explicable in terms of “habit structures”.

While the performance data discovered in behavioural science cannot be reduced to “description”, or “extraction of data”, or explained in terms of “habit structures”, behavioural scientists haven’t provided much by way of an explanation of how these capacities emerge. The reason that such an explanation is wanting is because of an uncritical reliance on Skinner’s crude pragmatist philosophy. However, pace Skinner, any attempt to explain emergent behavioural capacities will be reliant on a distinction between the emergent behaviours and the underlying capacities which make the behaviours possible. Any cogent explanation of emergent behaviours will rely on behavioural science adapting a distinction between competence and performance analogous to that recommended by Chomsky (1965). We will see later that some behaviourists are already moving in this direction when we discuss Hayes and Sanford 2014 later in the paper.

Theorists have long critiqued behaviourists for failing to adequately account for the distinction between competence and performance. For example, philosopher John Collins has argued that behaviourism is not a serious discipline because it doesn’t even try to explain the underlying capacities responsible for behaviour (Collins 2007 p. 883). Arguing further that a focus on competence doesn’t involve ignoring performance; rather it involves explaining performance, through explicating the mechanisms underlying linguistic competence (Ibid p. 883).

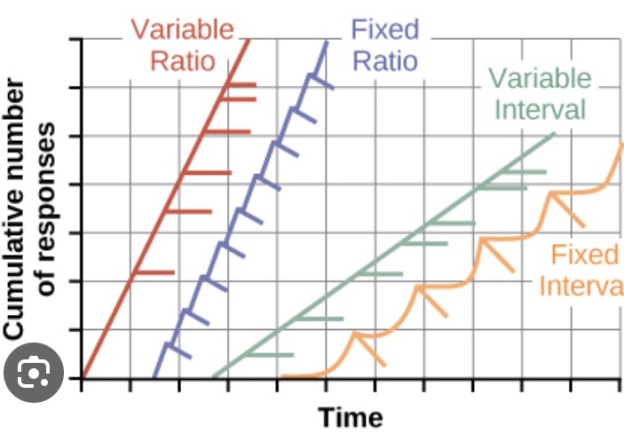

Collins’s claim that behaviourism is not a serious discipline is problematic. Experimental work in behaviourism over the last hundred or so years has yielded a wide range of experimental results which wouldn’t have been possible without research into behavioural science. The discovery of classical conditioning, and operant conditioning has revolutionized both psychology and biology. Since Chomsky wrote his ‘Aspects of a Theory of Syntax’ 60 years ago the field of behaviourism has continued to flourish demonstrating that it is a serious discipline which has made considerable advances over the last 60 years. Some discoveries in behavioural science of note have been Robert Rescorla’s discoveries of predictive mechanisms underlying classical conditioning (Rescorla 1969), the use of these predictive mechanisms to explain taste aversion in rats (Hayes & Sanford 2014), experimental literature demonstrating contingency insensitivity in rule following creatures (Galizio 1979, Shimoff et al 1981, Skinner 1984), the discovery of emergent stimulus equivalence (Sidman 1971), the discovery of emergent relational frames (Hayes & Thompson 1989) (Hayes 2001).

Even Skinner’s much maligned book ‘Verbal Behaviour’ has spawned hundreds of experiments on human subjects which have demonstrated some experimental control over his seven verbal operants (Sauter & Leblanc 2006). Likewise, behavioural science has demonstrated its use in applied disciplines, such as Applied Behavioural Analysis. So, any claim that behaviourism isn’t a serious discipline is conclusively refuted by the incredible predictive control it gives us over certain domains of interest.

Nonetheless, Collins does have a point. There is a reluctance of some in behavioural science to provide explanations of the behavioural patterns in terms of underlying competencies some of which may be innate. This reluctance doesn’t demonstrate that behaviourism isn’t a serious discipline, but it does pose serious limitations on the explanatory capacity of the discipline to account for the discoveries they make. Later in the paper I will explore some recent tentative attempts to explain competencies underlying our capacity to relation frame. I will argue that these competencies demonstrate that these tentative steps are a step in the right direction in bridging the gap between behavioural science and cognitive science.

What is Linguistic Competence?

When discussing Chomsky’s distinction between competence and performance it is typical to justify the distinction in terms of idealizations which usually occur in any discipline. When Chomsky is talking about linguistic competence, he notes that he is doing so using a series of idealizations which are necessary to understand the complex object under study:

“Linguistic theory is concerned primarily with an ideal speaker listener, in a completely homogeneous speech-community, who knows its language perfectly and is unaffected by such grammatically irrelevant conditions as memory limitations, distractions, shifts of attention and interest, and errors (random or characteristic) in applying his knowledge of the language in actual performance.” (Chomsky 1965 p. 3)[1]

A grammar will then be a description of the rules the idealized subject is using when understanding or speaking their sentences (Ibid p.4). Chomsky’s notion of an idealized subject’s competence is analogous to the idealizations which physicists use all the time to gain traction over the physical phenomena they are studying. A cliched example is of a physicist using idealizations such as studying a frictionless plane to give them an understanding of force and energy (Jackendoff 2002 p. 33).

Chomsky’s distinction between competence and performance which relies on idealizations is a sensible proposal and one which has led to success in gaining traction on the nature of language. While the use of idealizations is justified and common practice in science; Chomsky’s use of idealizations has had its critics. While most theorists would agree that some level of idealizations are needed it has been argued persuasively that Chomsky’s use of idealizations and his competence/performance distinction has ossified in such a manner as to make aspects of his theories irrefutable:

“Still, one can make a distinction between “soft” and “hard” idealizations. A “soft” idealization is acknowledged to be a matter of convenience, and one hopes eventually to find a natural way to re-integrate the excluded matters. A standard example is the friction of a frictionless plane in physics, which yields important generalizations about forces and energy. But one aspires eventually go beyond the idealization and integrate friction into the picture. By contrast, a “hard” idealization denies the need to go beyond itself; in the end it cuts itself off from the possibility of integration into a larger context…It is my unfortunate impression that, over the years, Chomsky’s articulation of the competence-performance distinction has moved from relatively soft…to considerably harder.” (Jackendoff 2002p. 33)

Other theorists have made similar points (Lakoff, G. 1987 p. 181, Palmer, D. 2023 p. 528).

Jackendoff isn’t arguing that we shouldn’t use idealizations or a competence-performance distinct rather he is warning of the possibility of an idealizing assumption becoming so hardened that it shields a theory from considering alternative ways of dealing with the data of experience. Thus, as we saw above Chomsky championed ignoring things like memory limitations, shifts of attention etc. But other work which doesn’t make this idealization actually use memory limitations to explain the hierarchical embedding in our language (Christiansen and Chater 2023, Christiansen and Chater 2016). Likewise, speech errors which Chomsky tells us to ignore in the name idealization have been used as productive data in explaining the cognitive processes underlying speech production (Hofstadter et al. 1989, Wijnen, F., 1992). Nonetheless, even Chomsky’s sternest critics would admit that his appeals to idealizations and the competence performance distinction have yielded interesting linguistic generalizations.

Jackendoff argued that the need for Chomsky to make the distinction between competence and performance was that other disciplines had failed to make the distinction:

“Chomsky makes the competence-performance distinction in part to ward off alternative proposals for how linguistics must be studied. In particular, he is justifiably resisting the behaviourists, who insisted that proper science requires counting every cough in the middle of a sentence as part of linguistic behaviour.” (Jackendoff 2002 p. 30).

While it is undeniable that behavioural science has a difficulty in explaining its own data because they do not always explain behaviour in terms of underlying competencies, nonetheless, Jackendoff in the above quote is engaging in a wild caricature of behaviourism.

Some behaviourists do obviously argue that that the subject matter they are interested in are actual instances of behaviour in a particular context (Palmer, D., 2023 p. 528). And in criticisms of Chomsky’s conceptions of linguistics they do argue that as behaviourists they are not obliged to explain possible sentences created by linguists which conform to the purported grammatical principles but never used in actual verbal behaviour. If speakers do not actually use such verbal forms while behaving in relation to each other the behaviourist considers it beyond their purview to explain them (Ibid, p. 529). But whatever one thinks of this behaviourist philosophy; it doesn’t entail the extremes that Jackendoff attributes to it.

Jackendoff attributes to behaviourists the view that scientists should “count every cough in the middle of a sentences as part of linguistic behaviour”. This claim amounts to the assertion that behaviourists do not think that scientists should use idealizations. This is an absurd accusation; any science which deprived itself of idealizations would be overwhelmed with complexity and wouldn’t be able get off the ground. It is simplifying idealizations which makes it possible for a scientific theory to gain any prediction and control.

But contrary to Jackendoff’s wild claim behavioural science was from the start engaging in idealizations. Studying Classical and Operant Conditioning in a laboratory setting was an idealization which assumed that these artificial experiments could explain the complex learning processes of animals in the wild. Furthermore, in his Verbal Behaviour Skinner used a variety of idealizations. Skinner divided language into seven main verbal operants and treated them separately and under different types of stimulus control. But he noted that this was an idealizing assumption and that in practice the verbal operants would be intertwined and could be acquired together (Skinner 1957 p. 188).

Furthermore, the notion of an operant was concerned with kinds of behaviour, that shared an effect on the environment and that, as a kind, are demonstrated to vary lawfully in their relations to other variables (Smith 1987 p. 289). Importantly, in his ‘Behaviourism and Logical Positivism’ Smith noted:

“The actual movements involved in pressing a lever, for example, might vary from instance to instance (e.g., left paw, right paw, nose), but they are equivalent with respect to producing reinforcement and they demonstrably function together in the face of changing conditions.” (ibid p. 289)

So even in the case of the operant itself idealisations are being used which results on the focus being on classes of behaviour[2]; so Jackendoff’s notion that behaviourists are engaging in “counting every cough” is simply absurd. Behavioural science like any other science is up to its eyes in idealizations from the start.

Nonetheless, while Jackendoff is incorrect in his assertion that behaviourists don’t use idealizations he is correct that behaviourists have sometimes eschewed using the notion of competence in their explications of language. And this lack of a theory of competence does hinder their ability to explain the behavioural data which they have discovered.

Behaviourists and Competence

Behaviourists by definition are concerned with behaviour. Hence, when Skinner wrote on language, he parsed this as the study of Verbal Behaviour. He divided language up into seven main verbal operants recommended empirically studying how various schedules of reinforcement maintained the use of these Verbal Operants. While he justified this research program in terms of studies which had been done on non-human animals; in the 70 years since Verbal Behaviour was written there has been hundreds of experimental studies on conditions responsible for maintaining the use of these Verbal Operants. Skinner’s theory is a paradigm case of an attempted explanation of human linguistic performance.

Subsequent Behaviourist Research has moved beyond Skinner’s claims about language, e.g. Galizio (1979), Sidman (1971), Hayes & Thompson (1989) and Hayes (2001). But they still focus on behaviour and the degree to which it can be predicted and controlled using conditioning. Much behavioural science has had a heavy emphasis on practical predictive control to aid in applied work. Thus, the Verbal Behaviour Approach inspired by Skinner is heavily involved in teaching functional communication to people with severe autism and or an Intellectual disability. Sidman’s work on Stimulus Equivalence sprung out of his work trying to teach people with an intellectual disability how to read. While relational frame theory is used in attempts to teach people with intellectual disabilities functional communication, as well as a tool in Acceptance Commitment Therapy. This emphasis on applied work is sometimes used as a justification for a heavy emphasis on prediction and control (Dymond & Roche pp. 220-221). From a philosophical point of view, this emphasis on prediction and control is justified by appeal to a pragmatic philosophy of the type espoused by Steven Pepper (1942).

This emphasis on pragmatic prediction and control of the organism clearly lays heavy weight on performance data; and the histories of reinforcement which shape this performance. But while the underlying competencies are not focused on, they do play a role in the explications. Skinner noted throughout his career that phylogenetic factors are important in shaping the organism:

“Just as we point to the contingencies of survival to explain an unconditioned reflex, so we point out to contingencies of reinforcement to explain a conditioned reflex.” (Skinner 1974 p. 43)

He emphasised that natural selection shaped the structure of the organism through the scythe of survival of the fittest, in analogous manner to the way operant conditioning shaped the behaviour of the organism through selection by consequence. In Skinner’s view selection by consequences rules in both phylogeny and ontogeny. And as early as the mid 60’s behaviourists the Breland’s were emphasising instinctive drift would ensure that different organisms would not be susceptible to have their behaviour shaped in the same way because of their different instinctive natures.

Analogously, Relational Frame Theorists don’t deny that any prediction and control we gain needs to be explained by underlying genetic, epigenetic, and neural structures. It is just that their primary emphasis is on emergent behavioural data which can be predicted and controlled through behavioural principles. Thus, while relational frames, are emergent phenomena discovered through behavioural training and testing, Hayes does try to explain their emergence as resulting from a combination of genetic constraints and social learning. Thus, he appeals to group selection favouring a cooperative instinct which makes the acquisition of relational frames such as coordination more likely and speculates on how other frames can be derived from a combination of coordination and equivalence (Hayes and Sanford 2014). Nonetheless, the primary emphasis in both relational frame theory and Skinnenarian behaviourism is on prediction and control of the organism using behavioural principles.

As discussed above Chomsky wasn’t against performance data per-se, on the contrary he believed that the only theory of performance of any theoretical interest was a theory which took on board competence-based insights (Chomsky 1965 p. 16). Chomsky’s claim has a degree of truth to it; but it is obviously not the whole story. As discussed above in the 60 years since Chomsky wrote Aspects behaviourists have discovered performance data which has ample theoretical interest. The performance data elicited by the behavioural tests, such as stimulus equivalence, rule following contingency insensitivity, relational frames are of great theoretical interest. But to yield a theoretically interesting theory of this performance data we will need to do so in terms of underlying competence systems.

Behaviourists sometimes do try to explain behaviour in terms of underlying competencies. As we saw above Skinner’s notion of phylogenetic shaping can be used to explain the Breland’s notion of instinctive drift, which is used in a theoretical explanation of animal’s divergent behaviour under schedules of reinforcement. Likewise, Quine appealed to a phylogenetically shaped similarity space which underlay our capacity to successfully engage in induction. However, when it comes to emergent phenomena such as stimulus equivalence and relational frames there has been a reluctance by some theorists to explain the phenomenon in terms of underlying innate mechanisms. In the next section I will give an example from psychological behaviourism which aims to explain relation framing in terms of evolved underlying competencies, and I will then discuss an example of a philosophical behaviourist explaining his data in terms of underlying competencies. This will be proof in principle that some behaviourists do make a distinction between competence and performance and do use idealizations in their theoretical endeavours.

Quine and Relational Frame Theory.

In this section I will outline and discuss an attempt by Hayes and Sanford (2014) to explain our species-specific capacity to engage in relational framing in terms of group selection for a cooperative instinct. This section will demonstrate that behaviourists do appeal to competencies to explain behavioural patterns to explain novel behaviour when necessary and that furthermore they routinely engage in idealizations to explain data. I will then further develop this point by showing how it isn’t just psychological behaviourists who appeal to underlying competencies and idealizations to explain behaviour. Some philosophical behaviourists do so as well. This will be demonstrated by evaluating Quines work in this area.

In Hayes and Sanford (2014) they discuss evolution of our ability to engage in verbal behaviour. To understand this capacity, they explain it in terms of abilities humans partially share with non-verbal creatures such as (1) the ability to use vocalizations to regulate the behaviour of others (shared with many mammals), (2) Social Referencing (dogs and Chimpanzees can do this), (3) Joint attention and non-verbal forms of perspective taking (chimps and apes) (4) Non-arbitrary Relational learning (all animals). And they argue that these competencies were modified through group selection. They note that a cooperative instinct within a group will give them the ability to out compete other groups.

With a Cooperative Instinct in place, if two humans are near an apple tree and both know how to say apple when they see an apple. If the apple is out of reach for person A and person A says “apple” then if it is within reach for person B then they will get it for person A. (Ibid p. 121). They argue that it would take the capacity of perspective taking along with the capacity for cooperation to bridge the gap between this epistemological triangle. They call this the beginning of a person’s capacity to engage in a frame of coordination. People acquire the ability to know that “apple” → apple and apple →”apple”. Thus, they know that the sound refers to the object and the object is referred to by the sound. This relationship can then come under contextual control of the “is” relation: Apple is “Apple” and “Apple” is Apple.

Deriving this relation of identity between the sound and the word will be helped through reinforcement for providing the object when the word is said, and having the object provided when you say the word. Relational Frame Theorists have argued that this ability to derive this frame (which is species specific), is made possible through coopting our capacities such as joint attention, the ability to modify others behaviours through vocalizations, social referencing, and non-arbitrary relation framing with our cooperative instinct.

Once this frame of coordination was acquired humans would then have the capacity to recognize mutuality in a frame. And they argue that repeated application of mutuality would give an organism the ability to use combinatorial entailment (ibid p.123). Thus, on this conception the capacity to relationally frame is created primarily by our cooperative instinct. So in effect they explain our capacity to relational frame in terms of underlying competencies such as social referencing, joint attention, the ability to control others using vocal signals, non-arbitrary relational responding being modified in terms of a human specific cooperative instinct shaped by natural selection. In this instance the novel performance data is explained in terms of underlying competencies. They aren’t just describing behavioural patterns they are explaining their arrival in terms of underlying competencies.

Quine Idealization

As discussed above the competence-performance distinction is aligned with the notion of idealizations where you can abstract out from aspects of a phenomenon and deal with more tractable subject matters. Thus, the scientist can be dealing with frictionless plans, or humans not subject to memory limitations or distractions etc. The charge made by Jackendoff, and others was that behaviourists don’t use idealizations and hence they have no resources to make the competence-performance distinction. We have seen that this is simply not true when it comes to behavioural science which from the start is up to its eyes in idealizing assumptions. This is true of not just of behaviourists in the scientific sphere but also of prominent behaviourists working on philosophical problems.

Quine’s conception of language is famously terse. While he talks of a child acquiring and being shaped by a language of his peers. He typically focuses on things such as observation sentences. There is little in his conception of language about other uses of language such as interrogatives. Quine justifies this because he is interested in language only in so far as it pertains to epistemology and ontology. Hence, he engages in an simplifying idealization when dealing with science. Thus in ‘The Roots of Reference’ Quine speaks of the fact that requesting makes up a large part of our linguistic usage, but he doesn’t account for it because it has little relevance in his attempts to explain how we acquire our scientific theory of the world (Quine 1973 p. 46). And later in the same book he notes that he doesn’t want a factual account of how children acquire English, rather he is concerned with telling a plausible story of how we go from infancy to developing a regimented language of science (ibid p. 92). Quine made the same point again in his Mind and Verbal Dispositions:

“One and the same little sentence may be uttered for various purposes: to warn, remind, to obtain possession, to gain confirmation, to gain admiration, or to give pleasure by pointing something out… somehow we must further divide; we must find some significant central strand to extract from the tangle…Truth will do nicely…a man understands a sentence in so far as he knows its truth conditions…this kind of understanding stops short of humour, irony, innuendo, and other literary values, but it goes a long way. In particular it is all we can ask of an understanding of science. (Quine 2008 pp. 448-249).

Again, we can see that Quine is abstracting away from various uses of language because they aren’t useful to him in sketching his story of how we go from stimulus to science. Quine, like his behavioural science colleagues, is engaging in idealizations at every step of his philosophical project. Furthermore, Quine is appealing to underlying competencies to explain how it is that humans go from stimulus to science (Quine 1980 p. 6, Quine 1989 p. 348, Quine 1998 p. 4). He appeals to innate similarity quality space to explain our ability to be able to differentially reinforced, an innate perceptual similarity space to explain our convergence on stimulus meaning, as well as appealing to body mindedness to explain children’s ability to understand object-permanence.

Conclusion

In this paper I have demonstrated that behaviourists of both philosophical and scientific bent do indeed make use of both idealizations and of a distinction between competence and performance in their work. Despite the criticisms of Chomsky and his followers; behaviourism’s focus on performance doesn’t necessitate them ignoring competence or shunning the use of idealizations. It is probable that the followers of Chomsky will be un-moved they will note that there has been no behavioural work which can account for the grammatical regularities which are discovered in linguistics. And this I would agree with. Behaviourism even modern behaviourism still hasn’t demonstrated that it has the conceptual resources to handle the syntax of natural language. Nonetheless, we are increasingly discovering more and more interesting performance regularities through behavioural research. These data do need to be explained in terms of underlying competencies. But the discovery of these interesting facts about our behaviour (including Verbal Behaviour), indicate that pace Chomsky we can discover interesting facts about performance prior to having a worked-out theory of competence. In fact, behavioural research has lead us towards achieving a greater understanding of the competencies underlying them not vice-versa. With the sciences of biolinguistics and behavioural science still in their infancies there is still a lot of data to acquire and experimental work to be done. But any attempts to understand either side will involve a greater attention to the what the practitioner of each discipline is doing and not relying on caricatures.

References

Barnes-Holmes, D. 2000. “Behavioural Pragmatism: No Place for Reality and Truth”, The Behaviour Analyst 23 pp. 191-202.

Barnes-Holmes, D. 2005. “Behavioural Pragmatism is A-Ontological, Not Anti-Realist: A Reply to Tonneau”, Behaviour and Philosophy 33 pp. 67-79.

Baum, W. 2002. “From Molecular to Molar: A Paradigm Shift in Behaviour Analysis”. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behaviour. 78 (1) pp. 95-116.

Chomsky, N. 1965. Aspects of a Theory of Syntax. MA: MIT Press.

Christensen, M, H, & Chater, N. “The Now-or-Never Bottleneck: A fundamental Constraint on language”. Behavioural and Brain sciences 39 (2016).

Christensen, M, H, & Chater, N. 2023. The Language Game. Random House. Penguin.

Collins, J. 2007. “Linguistic Competence Without Knowledge of Language”. Philosophy Compass 2 (6) pp. 880-895)

Dymond, S, & Roche, B, (2013) Advances in Relational Frame Theory. Context Press. New Harbinger Publications.

Galizio, M. (1979). “Contingency-shaped and rule-governed behaviour: Instructional control of human loss avoidance.” Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behaviour. 31, pp. 53-70.

Ginsburg, S., & Jablonka, E,. 2019. The Evolution of the Sensitive Soul. MIT Press. Cambridge MA.

Hayes, L, J, & Thompson, S. 1989. “Stimulus Equivalence and Rule-Following”. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behaviour. 52 (3) pp. 275-291.

Hayes, S, & Barnes-Holmes, D, & Roche, B. 2001. Relational Frame Theory: A post Skinnearian Account of Language and Cognition. Springer Science & Business Media.

Hayes, S. 2014. “Cooperation Came First: Evolution and Human Cognition.” Journal of the Experimental Analys of Behaviour 101 pp. 112-129.

Hofstadter, D, R, Moser avid J, M., “To Err is human; To study error-making is cognitive science”. Michigan Quarterly Review, 28 (2), pp. 185-215.

Jackendoff, R. 2002. Foundations of Language. Great Clarendon Street. Oxford University Press.

Kemp, G. 2017. “Quine, Publicity and Pre-Established Harmony”, Protosociology 34 pp. 59-72.

Lakoff, G. 1987. Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things. The University of Chicago Press.

Palmer, D. 2023. “Towards a Behavioural Interpretation of English Grammar.” Perspectives on Behaviour Science. 46 (3) pp. 521-538.

Pepper, S, C. 1942. World Hypotheses: A Study in Evidence. University of California Press.

Quine, W. 1953. From a Logical Point of View. Harvard University Press. Cambridge MA.

Quine, W. 1974. The Roots of Reference. La Salle. Open Court Press.

Quine, W. 1995. From Stimulus to Science. Cambridge. Mass. Harvard University Press.

Quine, W. 1996. “Progress on Two Fronts”, The Journal of Philosophy. 93/4 pp. 159-163

Quine, W. 2008. “The Flowering of Thought in Language” pp. 478-484 in Follesdal & Quine (EDS) Quine: Confessions of a Confirmed Extensionalist.

Rescorla, R. 1969. “Pavlovian Conditioned Inhibition.” Psychological Bulletin 72 (2) pp. 77

Sautter, R, & Leblanc L, “Empirical Applications of Skinner’s Analysis of Verbal Behaviour with Humans”. The Analysis of Verbal Behaviour 22 pp. 35-48.

Shimoff, E, Catania, A, Matthews, B, 1981. “Unstructured Human Responding: Sensitivity of Low Rate Performances to Schedule Contingencies.” Journal of Experimental Analysis of Behaviour. 36 (2) pp.207-220.

Sidman, M. 1971. “Reading and Auditory Visual Equivalences”. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 14 (1) pp. 5-13.

Skinner, B.F. 1957. Verbal Behaviour. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc.

Skinner, B.F. 1974. About Behaviourism. Knoph Doubleday Publishing Group.

Skinner, B.F. 1984. “Contingencies and Rules”. Behavioural and Brain Sciences. 7 (4) pp. 607-613.

Smith, L. D. 1986. Behaviourism and Logical Positivism: A Reassessment of The Alliance. California: Stanford University Press.

Wijnen, F, “Incidental word and sound errors in young speakers”, Journal of Memory and Language 31 pp.734-755.

Wilson, D, S, & Hayes, S. 2018 Evolution and Contextual Behavioural Science. Context Press. New Harbinger Publications Inc.

[2] There is a debate within behavioural science on whether scientists are studying of classes or individuals see Baum ‘From Molecular to Molar: A Paradigm Shift in Behaviour Analysis’ (2002).