Introduction.

From about 1950 there was a resurgence of interest in the Rationalist Empiricist debate. With people viewing Chomsky as an updated rationalist carrying on the traditions of Leibniz and Descartes and Quine and Skinner updated versions of empiricism carrying on the traditions of Locke and Hume. And a consensus emerged that Chomsky’s rationalism won out over the empiricism of Quine and Skinner.

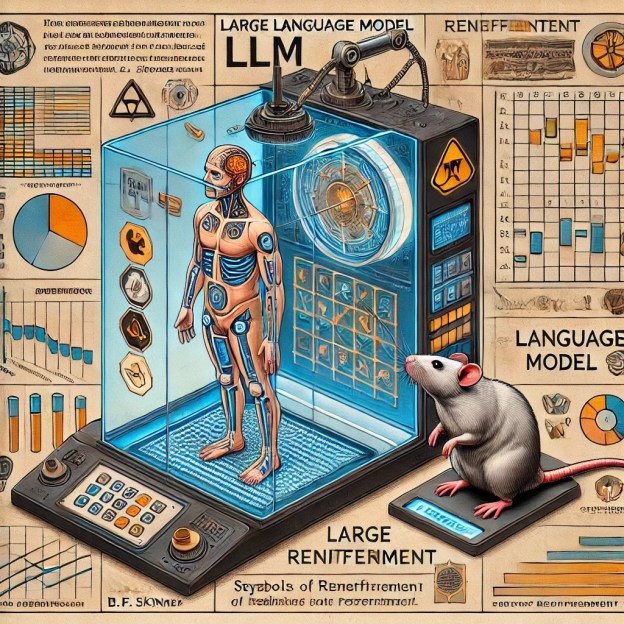

In recent years with the rise of Deep Convolutional Neural Networks, and Large Language Models some have argued that their architecture is data driven and hence they are an existence proof that empiricist learning is a viable way of modelling the mind (Bunker, C 2018). Prompting debate where others argue that these models don’t vindicate any kind of empiricism as they rely on innate architecture.

In this paper my focus will be LLMs because their linguistic capacities make them directly relevant to the earlier debates between Chomsky, Quine and Skinner. And evaluate whether LLMs do indeed vindicate a type of empiricism. I will argue that LLMs are too dissimilar to human cognitive systems to be used as a model for human cognition. They make bad models of both human linguistic competence and human linguistic performance. So, I argue that they offer no vindication of empiricism (or rationalism for that matter).

Chomsky and Quine and the Rationalist-Empiricist Debate.

Famously the rationalist-empiricist debate between people such as Locke and Descartes which focused on subjects such as whether humans were born with innate concepts, was revisited in the 1950s. When Noam Chomsky burst onto the scene with his review of Skinner’s book Verbal Behaviour to many this was viewed as a reviving of the rationalist-empiricist debate. Chomsky entitled his 1966 book ‘Cartesian Linguistics: A Chapter in the History of Rationalist Thought’, thus setting himself up as the heir apparent to Descartes rationalism.

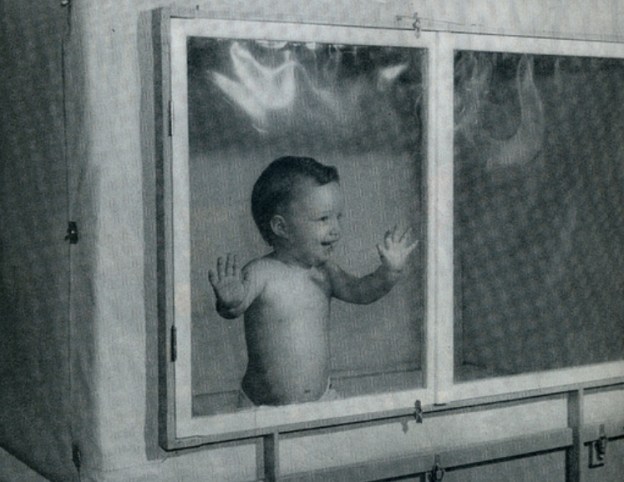

In Skinner’s Verbal Behaviour he divided language up into seven Verbal Operants which he argued are controlled using his three-term contingency of antecedent behaviour and consequence. Chomsky criticized Skinner for taking concepts from the laboratory where they were well understood from animal literature and extending them into areas where there was no such experimental evidence. He charged Skinner with either using the technical terms literally in which his views were false, or metaphorically in which case the technical terms were as vague as ordinary terms from folk psychology.

In his 1965 book ‘Aspects of a Theory of Syntax’ Chomsky made his famous distinction between competence and performance. Chomsky argued that the only substantive theory of performance which would be possible would come via theory of underlying competence. And he illustrated this point through showing how elements from our underlying grammatical competence could predict and explain aspects of our linguistic performance. Since behaviourism was obviously primarily concerned with behaviour many viewed Chomsky’s competence performance distinction as an attack on behaviourism. Many scientists influenced by Chomsky argued that behaviourists not having a competence-performance distinction meant that it couldn’t be taken seriously as a science (Jackendoff 2002, Collins 2007).

Chomsky (1972, 1986) poverty of stimulus argument was deemed a further dent in the behaviourist project. Chomsky used the structure dependence syntactic movement such as auxiliary inversion as an example of syntactic knowledge which a person acquired even though a person could go through much or all their life without ever encountering evidence for the construction. The argument being if the child learned the construction despite never encountering evidence for its structure. And the child didn’t engage in trial-and-error learning where he tried out incorrect constructions which were systematically corrected by his peers until he arrived at the correct one (Crain and Nakayama 1987, Brown and Hanlon 1970). Then knowledge of the construction must be built into the child innately.

Theorists viewed poverty of stimulus arguments as further evidence that the behaviourist project was doomed to failure. With many contrasting Chomsky’s emphasis on innate knowledge with Skinner’s supposed blank-slate philosophy (Pinker 2002). Thereby situating Skinner as a modern-day Locke battling with a modern-day Descartes (Chomsky), and the consensus was that modern science had shown that the rationalist position was the correct one.

Quine and Chomsky.

The debate between Chomsky and Skinner was primarily focused on issues in linguistics, and psychology. In philosophy the rationalist-empiricist debate played out in a debate between Quine and Chomsky. Quine billed himself as an externalized empiricist whose primary aim was to explain how humans go from stimulus to science in a naturalistic manner. His entire project centred on naturalising both epistemology and metaphysics. On the epistemological side of things his need to explain how we go from stimulus to science would involve psychological speculations on how we acquire our language, how we develop the ability to refer to objects. Quine was explicit in these speculations that any linguistic theory was bound to be behaviourist in tone since we acquire our language through intersubjective mouthing of words in public settings. This commitment to behaviourism set Quine at odds with Chomsky.

In 1969 Chomsky’s wrote a criticism of Quine called ‘Quine’s Empirical Assumptions’. This criticism noted that Quine’s notion of a pre-linguistic quality space wasn’t sufficient to account for language acquisition. That Quine’s Indeterminacy of Translation Argument was trivial and amounted to nothing more than ordinary Underdetermination. And that Quine’s invocation of the notion of the probability of a sentence being spoken was meaningless.

Skinner never replied to Chomsky[1] arguing that Chomsky so badly misunderstood his position that further dialogue was pointless. But Quine (1969) did reply; in his reply he charged Chomsky with misunderstanding his position and of attacking a strawman. On the issue of a prelinguistic quality space he argued that it was postulated as a necessary condition of acquiring the ability to learn from induction or reinforcement; he never thought it was a sufficient condition of our acquiring language. Quine argued that “the behaviourist was knowingly and cheerfully up to his neck in innate apparatus”. He further argued that indeterminacy of translation was additional to underdetermination and revealed difficulties with linguists and philosophers’ uncritical usage of “meanings, ideas and propositions”. And finally, he noted that Chomsky misunderstood Quine’s discussion of the probability of a sentence being spoken. Quine wasn’t speaking about the absolute probability of a sentence being spoken, rather he was concerned with the probability of a sentence being spoken in response to queries in an experimental setting.

This led to a series of back and forth between Chomsky and Quine. In his (1970) ‘Methodological Reflections on Current Linguistic Theory’, Quine criticized Chomsky’s notion of implicit rule following. Quine noted that there are two senses of rule-following he could make sense of (1) Being guided by a rule: A person following a rule they can explicitly state, (2) Fitting a Rule: A person’s behaviour can conform to any of an infinite number of extensionally equivalent rules. But Quine charged Chomsky of appealing to a third type of rule (3) A rule that the person cannot state, but is nonetheless implicitly following, and this rule is a particular rule distinct from all the other extensionally equivalent rules that the persons behaviour conforms to. Chomsky (1975) correctly responded that Quine was again arbitrarily assuming that underdetermination was somehow terminal in linguistics but harmless in physics. As Chomsky approach became less about rules and more to do with parameters switching Quine’s rule-following critique had less and less traction.

While Chomsky’s critique of Skinner achieved the status of almost a creation myth in cognitive science. With most introductory texts in psychology or cognitive science attributing the Chomsky’s review of Verbal Behaviour being the death-knell of behaviourism and the birth of cognitive science. Whereas Chomsky’s criticism of Quine wasn’t as well known, and it had a more nuanced reading. While a lot of people came to the view that Chomsky won the debate; it didn’t attain the creation myth status that the review had. Nonetheless, it is fair to say that most philosophers, accepted Chomsky’s criticisms of Quine as to the point.

Outside of the realm of academic debates in the popular press when Skinner is spoken about, he is referred to a blank slate theorist (Pinker 2002). With Skinner and to a lesser degree Quine placed in the camp as exemplars of the empiricist tradition and modern-day inheritors of John Locke’s mantal, and Chomsky a self-described exemplar of the Cartesian Tradition. And the scientific consensus is that Chomsky’s rationalism has won out over Quine and Skinner’s empiricism.

Artificial Intelligence and Empiricism.

In recent years with AI getting more and more sophisticated; philosophers, psychologists, and linguists have begun to explore what these AI systems tell us about the rationalist-empiricist debate. With some theorists arguing that empiricist architecture is responsible for the success of recent AI systems (Buckner 2017, Long, 2024). While others have argued that in fact the architecture because it needs in built biases in fact supports rationalism (Childers et al 2020 p.87).

Buckner (2017) argued that deep convolutional neural networks are useful models of mammalian cognition. And he further argued that these DCNNs use of “transformational abstraction”, vindicated Hume’s empiricist conception of how humans acquire abstract ideas. Childers et al (2020) have hit back at this view and have argued both that LLMs and DCNNs require built in biases for them to be successful. And they further argue that the need for built in biases, is analogous to the way Quine needed to posit innate knowledge to explain language acquisition, thereby, according to them, undermining their empiricist credentials (Childers et al 2020 p. 72).

Childers et all’s reading of the rationalist empiricist debate is extremely idiosyncratic. Their assertion that the postulation of any innate dispositions is an immediate weakening of empiricism is bizarre (Ibid p. 84). This reading of the rationalist-empiricist dispute doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. Hume, and early arch-empiricist needed innate formation principles in the human mind to account for how we combine the ideas we receive from impressions into complex thoughts (Fodor 2003). And even Chomsky who is viewed as a paradigm exemplar of the rationalist tradition argued that innateness wasn’t the issue when it came to the rationalist-empiricist debate:

The various empiricist and behaviourist approaches mentioned postulate innate principles and structures (cf. Aspects, pp. 47 f.). What is at issue is not whether there are innate principles and structures, but rather what is their character: specifically, are they of the character of empiricist or rationalist hypotheses, as there construed?” (Katz & Chomsky: 1975).

“…Each postulates innate dispositions, inclinations, and natural potentialities. The two approaches differ in what they take them to be…The crucial question is not whether there are innate potentialities or innate structure. No rational person denies this, nor has the question been at issue. The crucial question is whether this structure is of the character of E or R; whether it is of the character of “powers or “dispositions”; whether it is a passive system of incremental data processing, habit formation, and induction, or an “active” system which is the source of “linguistic competence” as well as other systems of knowledge and belief” (Chomsky 1975 pp. 215-216)

And Watson, Quine and Skinner were consistent about this point throughout their careers: Wason 1924 p. 135, Skinner 1953 p. 90, Skinner 1966 p. 1205, Quine 1969 p. 57, Quine 1973 p. 13, Skinner 1974, p.43.

The point of Childers et all’s criticism was that Hume’s empiricism with its appeal to a few laws of association., needed to be supplanted by Kant’s system which postulated many more innate priors (Childers et al 2020 p. 87). This may have been a problem of Hume, but it is no difficulty for the likes of Quine who was an externalized empiricist who had no issues whatsoever with innate priors once they could be determined experimentally (Quine 1969 p. 57). When it comes to Artificial Intelligence there is a legitimate debate on whether it is pragmatic to build the systems on rationalist or empiricists principles. But this only has relevance to the rationalist empiricist debate if it can be demonstrated that artificial intelligence systems learn in the same way as humans do. In the next section I will evaluate how closely AI systems model human cognition. To do this I will focus LLMs and the degree to which they accurately model human linguistic cognition.

Large Language Models and Human Linguistic Competence.

Theorists have argued that the similarities between LLMs output and human linguistic output make LLMs and the way they learn directly relevant to theoretical linguistics. Thus, Piantadosi (2023), has argued that LLMs refute central claims made by Chomsky et al in the generative grammar tradition about language acquisition. This comparisons of LLMs to actual human cognition has been challenged in the literature (Chomsky et al 2023, Kodner et al 2024, Katzir, R 2023). In this section I will consider various disanalogies between LLMs and Human linguistic cognition which makes any comparison between problematic. And in the final section I will consider the relevance of these disanalogies towards considering work in AI as being pertinent to debates about Rationalism versus Empiricism.

Poverty of Stimulus Arguments, Artificial Intelligence, & Human Linguistic Capacities.

A clear disanalogy to human linguistic abilities and LLMs is that humans acquire their language despite a poverty of stimulus, while LLMs learn because of a richness of stimulus (Kodner et al 2023, Chomsky et al 2023, Long, R 2024, Marcus, G. 2020). To see the importance of this distinction a brief discussion of the role that Poverty of Stimulus Arguments have played in linguistics is necessary with this in place we can return to the stimulus which LLMs are trained on.

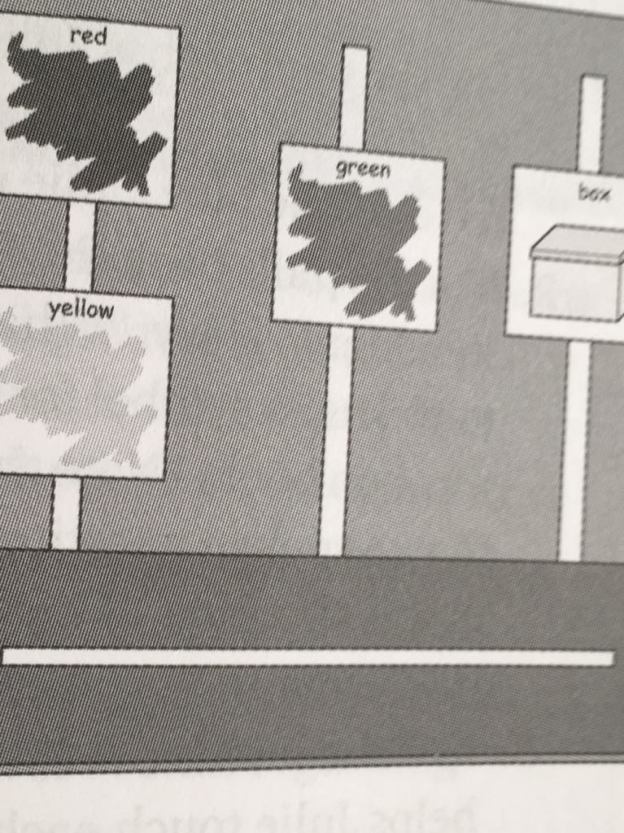

Chomsky 1965 noted that people acquire syntactic knowledge despite a poverty of stimulus. Humans are exposed to limited fragmentary data and still manage to arrive at a steady state of linguistic including knowledge of syntactic rules which they may not have ever encountered in their primary linguistic data. Chomsky used auxiliary inversion as his paradigm example of a poverty of stimulus (Chomsky 1965, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1975, 1986, 1988[2]). Pullum and Scholz (2002) reconstructed Chomsky’s Poverty of Stimulus Argument as follows:

- Humans learn their language either through data driven learning or innately primed learning.

- If humans acquire their first language through data driven learning, then they can never acquire anything for which they lack crucial evidence.

- But Infants do indeed learn things for which they lack crucial knowledge.

- Thus, humans do not learn their first language by means of data-driven learning.

- Conclusion: humans learn their first language by means of innately primed learning (Pullum and Scholz 2002).

Pullum & Scholz (2002) Isolated premise three as the key premise in the argument. And they sought empirical evidence to discover the amount of times constructions with evidence for auxiliary occur in a sample of written material. The material they choose to examine was Wall Street Journal back issues. They also estimated the amount of linguistic data a person is on average exposed to do. To do this they relied on Hart and Risely (1997) ‘Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experiences of Young Children’. They estimated that your average child from a middle-class background will have been exposed to about 30million word tokens by the age of three. Pullum and Scholz argue that the child will have been exposed to about 7500 relevant examples in three years. Which amounts to about 7 relevant questions per day. But a primary criticism of their work was that the Wall Street Journal wasn’t representative of the type of data that a child would be exposed to. Sampson 2002 searched the British National Corpus and argued that the child would be exposed to about 1 relevant example every 10 days.

But the next question was whether a child would be able to learn the relevant construction from 1 example every 10 days (Lappin & Clark 2011). Reali and Christensen (2005) Perfors, Tenebaum & Reiger (2006) have all constructed mathematical models demonstrating that children are capable of learning from the above amounts of data. However, Berwick & Chomsky et al. (2011) in their ‘Poverty of Stimulus Revisited’ have hit back arguing that Auxiliary Inversion is meant as an expository example to illustrate the APS to the general public. And that there are much deeper syntactic properties which children could not learn from the PLD. The debate still rages on, but it is still a consensus in generative grammar that the Poverty of Stimulus is a real phenomenon which humans need domain specific innate knowledge to overcome.

As our discussion above indicates that there has been some push back against Poverty of Stimulus Arguments however it is still the default position in linguistics. Furthermore, even those who push back against the APS would gleefully admit that the linguistic data a LLM is trained on is not analogous to the Primary Linguistic Data of your average child. Children are exposed to 10million tokens a year, LLMs are exposed to around 300 billion tokens and this number is increasing exponentially (Kodner et al 2024). So, while the output of a LLM and a human may be roughly analogous the linguistic input they receive is in no way analogous.

Competence & Performance in LLMs & Humans.

The divergence on linguistic data which LLMs and humans are trained on is a clear indicator that they work of different underlying competencies. Other differences emerge in terms of the materials they use. In terms of computation considerations chips are faster than neurons (Long 2024). To the degree that outputs are similar that doesn’t prove that they rely on the same underlying competencies (Firestone 2020, Kodner et al 2024, Milliere & Buckner 2024). Kodner et al give the example of two watches both of which keep time accurately but one of which is digital, and the other is mechanical. Despite similar performances they achieve it through different underlying competencies (Kodner et al 2024).

But Are Human and LLM Outputs Analogous?

The question of whether Humans and LLM’s output are analogous is obviously vital if we want to understand whether they operate using the same underlying competencies. We have already seen that the two systems seem to learn differently one despite the poverty of stimulus and one because of the richness of stimulus. This points towards different underlying innate competencies. Different underlying competencies aside the next section will demonstrate that the performances of each system are very different.

At a superficial level it LLMs and Human outputs appear very similar. Chat GPT-4 can to some degree fool a competent reader into thinking that a human produced the outputted sentences. Clark et al (2021) studied human created stories, news articles, and texts and got a LLM to create similarly sized stories. 130 participants were tested, and they couldn’t tell apart the human from LLM models at a range greater than chance. (Scwitzgebel et al 2023). Scwitzgebel, et al (2023) Created a Large Language Model which was able to simulate Daniel Dennett’s writing style and though experts were able to distinguish amongst them at rates barely above chance, it was surprising how close run the thing was given the fact was that it was scholars who were experts on Dennett who were being probed.

While a LLM can construct sentences which appear to be analogous to ordinary human sentences there are obviously a lot of disanalogies. While LLMs can reliably produce syntactically sound sentences and sentences which are semantically interpretable. The words the LLM use have no meaning to the LLMs only to the humans that interpret their output. The reason that they have no meaning is because they are not grounded in sensory experience for the LLM. Whereas for humans they obviously are (Harnard 2024). The LLM unlike the human isn’t talking about any state of affairs in the world, rather it is merely grouping together tokens according to how the tokens are fed into it in its training data.

When criticisms are made that LLMs outputs don’t have meanings. We need to be careful how we parse these statements. Obviously, they have meaning in the sense that they can distinguish between two sentences which are syntactically identical, but which don’t have the same meaning. But the sentences do not have meaning in the sense of referential relation between the words and a mind independent reality. However, given that the idea of explicating meaning in terms of a word-world relation has been questioned (Chomsky 2000, Quine 1973), it is difficult to know what to make of the claim that LLMs don’t have meanings because their words don’t refer to mind independent objects.

Bender & Koller (2020) used a thought experiment to illustrate why they believed that LLMs did not mean anything when they responded to queries. The thought experiment imagines two people trapped on different Islands who are communicating with each other via code through a wire which is stretched between the islands via the ocean floor. In this thought experiment an Octopus who is a statistical genius accesses the wire and can communicate with the other people on the island through pattern recognition. But though he is able to figure out what code to use, and when, due to the context of the code being used and the patterns of when they are grouped together, he has no understanding of what is being said. Bender & Koller argue that if a person on the Island asked the Octopus how to build a catapult out of coconut and wood he wouldn’t know how to answer because he has no real-world knowledge of interacting with the world and is instead merely grouping brute statistical patterns together.

Piantadosi & Hill (2023) in their “Meaning Without Reference in Large Language Models”, argue that thought experiments such as the Octopus one fail because it makes the unwarranted assumption that meaning can be explicated in terms of reference. They argue that meaning cannot be explicated in terms of reference for the following reasons:

- There are many terms which are meaningful to us, but which have no clear reference e.g. Justice.

- We can think of concepts of non-existent objects. These have meanings but don’t refer to anything in the mind-independent world.

- We have concepts of impossible objects such as a round square, perpetual motion machine,

- We have concepts which pick out nobody, but which are meaningful: e.g. the present King of Ireland.

- We have concepts which have meaning but which don’t refer to concrete particulars e.g. concepts of abstract objects.

- We have terms which have different meanings but the same reference {morning star-evening star}.

They go on to argue that conceptual role theory in which meaning is determined in terms of entire structured domains (like Quine’s web-of-belief) plays a large role in our overall theory of the world. But they do nonetheless acknowledge that reference plays some role in grounding our concepts. Just not as large a role as some theorists criticizing LLMs believe. They are surely right that as theory of the world becomes more and more sophisticated our theory will, as Quine noted, face empirical checkpoints only at the periphery. Nonetheless, when humans are acquiring their language in childhood they must go through a period where they learn to use the right word in the presence of the right object, and to somehow learn to triangulate with their peers in using the same word to pick out a common object in their environment.

As we saw above Piantadosi & Hill (2023) shared concerns about crude referentialist theories of meaning and their relation to LLMs, but they did acknowledge that there are word-world connections between some words and objects in the mind independent world. Quine famously tried to connect our sentences to the world through his notion of an observation sentences. He argued that an observation sentence was a sentence which members of a verbal community would immediately assent to in the presence of the relevant non-verbal stimuli.

But Quine immediately ran into a difficulty with this approach. The difficulty stemmed from the fact that Quine found it hard to say why different members of a speech community assented to an observation sentence. Quine tried to cash out the meaning in terms of stimulus meaning where a particular observation sentence was associated with a particular pattern of sensory receptors being triggered. But this made intersubjective assent on observation sentences difficult to explain given that different subjects would obviously have different patterns of sensory receptors triggered in various ways in response to the same observation sentences. What pattern of sensory receptors was triggered by what observation sentences would be largely the result of each subject’s long forgotten learning history. All of this made it difficult to see how Quine could make sense of a community assenting to an observation sentence being used in various circumstances.

Quine eventually made sense of intersubjective assenting to an observation sentence by appealing to the theory of evolution. He argued that there was a pre-established harmony between our subjective standards of perceptual similarity and trends in the environment. And that humans as a species were shaped by natural selection to ensure that they shared perceptual similarity standards. This fact was what made it possible for humans to share assent and dissent to observation sentences being used in certain circumstances.

For Quine shared perceptual similarity standards and reinforcement for using certain sounds in certain circumstances gave observation sentences empirical content. But to achieve actual reference Quine argues that we need to add things like quantifiers, pronouns, demonstratives etc. The key point is though that observation sentences link with the world (even if in a manner less tight than objective reference), because of our shared perceptual similarity standards matching objective trends in our environment. This is what makes intersubjective communication possible. LLMs are not responsive to the environment in anything like the way humans are when they are acquiring their first words. Even prior to humans learning the referential capacities of language, children using observation sentences are still in contact with the world. To this degree then Piantadosi & Hill’s concerns about reference are besides the point. As humans begin to acquire their first words, they do so through observation sentences which are connected our environment. The fact that when we acquire a language complete with words and productive syntax we can speak about theoretical items, fictional items, impossible objects etc is interesting but doesn’t speak to the LLM issue. The fact is that as humans first acquire their words they do so in response to their shared sensory environment. LLMs do not learn in this way at all. Their training is entirely the result of exposure to textual examples which they group into tokens based on the statistical likelihood of textual data occurring together. So, while humans eventually learn to speak about non sensorially experienced things their first words are keyed to sensory experience, and this is a key difference between them and LLMs. In the next section I will consider some objections view but firstly I want to recap what we discussed so far.

Interlude: Brief Recap.

Thus far we have considered the Rationalist-Empiricist debate as it played out in debates between Skinner, Quine and Chomsky. Noting that the consensus is that Chomsky’s rationalism won the day over the empiricism of Quine and Skinner. In recent years with AI getting more and more sophisticated a resurgence of interest has occurred on AI and its relation to the rationalist-empiricist debate. With some theorists arguing that modern AI indicates that empiricist theories of cognition are, contrary to what was previously believed, being realized by some current AI. Following this I discussed whether this was the case, relating it to previous debates in the rationalist-empiricist debate. Arguing that contrary to Childers et al, an AI can learn in an empiricist manner even does so via built in constraints. With this being argued I then questioned whether the fact that some AI learned in a particular manner had much of an impact on human cognition. To sharpen the issue, I narrowed the debate down to whether if LLMs learned in an empiricist manner this would tell us much about the rationalist-empiricist debate in humans.

To decide on this issue, I considered whether LLMs and humans learned in the same manner. Concluding like many others that they learn in entirely different ways. Humans learn despite the poverty of stimulus while LLMs learned because of the richness of their stimulus. I argued that the different manners in which they learned indicated that there were probably different competencies underlying their respective performances.

AI and the Relevance of Rationalism and Empiricism.

Above we discussed some disanalogies between LLMs and human linguistic capacities. Two main differences were noted (1) Differences in the stimulus needed for the respective agents to acquire language, which indicates different underlying competencies. (2) LLMs language is not grounded, and Human language is grounded; and this difference is a result of the different ways in which they acquire their language, humans begin by being responsive to the world in a triangular relation with others, while the LLM acquires their language through statistical grouping of text they are trained on.

So given that humans and LLM’s outputs are the result exposure to different quantities, and types of data, which indicate different underlying competencies, a question arises as to the relevance of AI to understanding human linguistic capacities. Earlier we discussed the debate between Chomsky and Skinner & Quine and its relation to current debates on the nature of LLMs. But given the disanalogies we have noted between LLMs and humans it is questionable whether they have anything to tell us about the rationalist-empiricist debate at all.

The debate between the rationalists and empiricists was never centred on whether innate apparatus was necessary for a creature to learn a particular competency. All sides of the debate agreed that some innate apparatus was necessary to explain particular competencies, and the degree of the innate apparatus which need to be postulated is to be determined empirically. The empiricist position was one which argued that humans learned primarily through data driven learning (supported by innate architecture), while the rationalist argued that humans learned through innate domain specific competencies being triggered by environmental input.

However, given the differences between LLMs and Human’s linguistic competencies their relevance to each other on the rationalist-empiricist debate is in doubt. Even if we can conclusively demonstrate that a LLM or a DCNN learns in an empiricist manner, this will not tell us anything about whether humans learn in an empiricist manner. Because human competencies are so different than a LLMs it is simply irrelevant to the rationalist-empiricist debate whether LLMs learn in an empiricist manner or not.

It is theoretically possible that a philosopher could argue a la Kant that any form of cognition will a priori need to implement innate domain specific machinery to arrive at its steady state. And one could offer empirical data to support this a priori claim by showing that very different forms of cognition e.g. human and LLMs both learn by implementing innate domain specific architecture. But this isn’t how the debate has been played out in the literature. Typically, the literature argues that LLMs are largely empiricist, and this fact vindicates empiricism in general, or it is argued that they are largely rationalist, and this fact vindicated rationalism. I have argued here that given the very different nature of LLMs and humans it is irrelevant to the question of how humans acquire their knowledge whether LLMs are rationalist or empiricist.

But this isn’t to say that it is unimportant whether LLMs or other forms of AI learn in a rationalist or an empiricist manner. There are still practical issues in engineering as to whether one is more likely to be successful in building things like Artificial General Intelligence using empiricist architecture or not. Thus, people like Marcus (2020) argue that while we may be able to build AGI using empiricist principles, we will not be able to build AGI unless we build in substantial innate domain specific knowledge into the system. Marcus even argues that the best way to understand what innate architecture is necessary to be built into our AI models we should look to our best example of an organism with general intelligence, i.e. Humans.

While the engineering question is extremely interesting from a practical point of view and could motivate an interest in whether LLMs or other types of AI learn in a rationalist or an empiricist manner. But when it comes LLMs, the question of whether they learn in an empiricist, or a rationalist manner is largely irrelevant to the rationalist-empiricist question in relation to humans.

Bibliography

Berwick, R, & Pietroski, P, & Chomsky, N. 2011 “Poverty of the Stimulus Revisited.” Cognitive Science. Vol 35. Issue 7 pp. 1207-1242.

Bender & Koller. (2020) “Climbing Towards NLU: On Meaning, Form and Understanding in the Age of Data.” Proceedings of the 58th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics.

Brown, R. & Hanlon, C. 1970. “Derivational complexity and order of acquisition in child speech.” In Hayes, J.R. (eds). Cognition and the Development of Language. New York Wiley.

Buckner, C. 2018. “Empiricism without Magic: Transformational Abstraction in Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Synthese. Vol 195 pp. 5339-5372.

Childers, T, & Hvorecky, J, & Majer, O. 2023. “Empiricism and the foundations of Cognition”. AI and Society. Vol 38 pp. 67-87.

Chomsky, N. 1959. “A review of B.F. Skinner’s Verbal Behaviour”. Language, 35. PP 26-57.

Chomsky, N. 1965. Aspects of a Theory of Syntax. MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. 1966. Cartesian Linguistics. New York: Harper & Row.

Chomsky, N. 1969. “Quine’s Empirical Assumptions”. Synthese 19 pp. 53-68.

Chomsky, N. 1975. Reflections on Language. New York: Random House.

Chomsky, N. 1986. Knowledge of Language: Its Nature, Origin and Use. New York, New York: Praeger.

Chomsky, N. 2000. New Horizons in the Study of Language and Mind. Cambridge: MA.

Chomsky, N, Roberts, I, Watumull, J. 2023. “The False Promise of ChatGPT.” The New York Times.

Chomsky, N & Katz, J. 1975. “On Innateness: A Reply to Cooper.” Philosophical Review. 84 pp. 70-84.

Clark, L & Lappin, S. 2011. Linguistic Nativism and the Poverty of the Stimulus. Wiley

Collins, J. 2007. “Linguistic Competence Without Knowledge of Language”. Philosophy Compass 2 (6) pp. 880-895

Crain, S & M, Nakayama. 1987. “Structure Dependence in Grammar Formation”. Language, Vol 63 pp. 522-543.

Firestone, C. (2022) “Competence and Performance in Human Machine Comparisons.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117. 43. Pp. 25662-26571.

Fodor, J. 2003. Hume Variations. Oxford University Press.

Hart, B & Risley, T, & Kirby, J. 1997. “Meaningful differences in the everyday experiences of the young American.” Canadian Journal of Education. Vol 22. Issue 3.

Harnard, S. 2024. “Language Writ Large: LLMs, ChatGPT, Grounding, Meaning, and Understanding.”

Jackendoff, R. 2002. Foundations of Language. Great Clarendon Street. Oxford University Press.

Katzir, R. 2023 “Are Large Language Modules Poor Theories of Linguistic Cognition: A Reply to Piantadosi”.

Kodner, J, & Payne, S, & Heinz, J. 2023 “Why Linguistics will thrive in the 21th Century: a reply to Piantadosi”.

Long, R. 2024. “Nativism and Empiricism in Artificial Intelligence”. Philosophical Studies. Vol 181 pp 763-788.

Marcus, G. 2020. “The Next Decade in AI: Four Steps Towards Robust Artificial Intelligence”

Mollo, D, & Milliere, R. “The Vector Grounding Problem”.

Milliere, R & Buckner C. 2024. “A Philosophical Introduction to Language Models: Part 2”.

Piantadosi, S. 2023 “Modern Language Models Refute Chomsky’s Approach to Language.”

Piantadosi, S, & Hill, F. 2023 “Meaning with our Reference in Large Language Models”.

Pinker, S. 2002. The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. New York Viking.

Pullum, G, K. & Scholz, B. 2002 “Empirical assessment of stimulus poverty argument.” The Linguistic Review. 19 pp. 9-50.

Quine, W. 1968. “Reply to Chomsky”. Synthese 19 pp. 274-283.

Quine, W. 1970. “Methodological Reflections on Current Linguistic Theory”. Synthese 19, pp. 264-321.

Quine, W. 1974. The Roots of Reference. La Salle. Open Court Press.

Sampson, G. 2002. “Exploring the Richness of the Stimulus”. The Linguistic Review. 19 pp. 73-104.

Schwitzgebel, E, & Schwitzgebel, D, & Strasser, A. 2024. “Creating a Language Model of a Philosopher”. Mind & Language. 32 (2) 237-259.

Skinner, B.F. 1957. Verbal Behaviour. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc.

[1] For an interesting reply on Skinner’s behalf see Kenneth McCorquodale.

[2] In the following I am Pullum and Scholz (2002) ‘Empirical Assessment of Stimulus Poverty Arguments.