Introduction

In this blogpost I will discuss a 2001 paper by Wilson et al ‘Hume’s psychology contemporary learning theory and the problem of knowledge amplification’. The primary claim of their paper was that Hume’s speculations about how we acquire our theory of the world can be updated and made more precise using evidence from contemporary behavioural science. A barrier to using behavioural science to update Hume’s philosophy was that behavioural principles such as Operant and Classical Conditioning are shared by most living creatures and all mammals, so they don’t give us an obvious explication of human specific capacities. Wilson et al argue that the discovery of relation frames; in particular, the human specific capacity to achieve stimulus equivalence, as well as relations of hierarchy, coordination etc helps us explicate the higher reaches of human cognition, such as our capacity for verbal behaviour.

I will argue that while their project shares much in common with Quine’s earlier attempt to naturalize our epistemology there are some differences between the two projects. In particular, the pragmatist philosophy which underlies the contextual behavioural science is at odds with Quine’s more mechanistic view. Quine thinks of behaviour as evidence to be used to discover underlying mechanisms while Contextual Behavioural Scientists are primarily concerned with whole organism environmental interactions and deriving techniques to achieve prediction and control over such organisms.

Finally, I will argue that Contextual Behavioural Science offers us a more complete account of our capacity to acquire verbal behaviour than Quine managed and hence is a more complete account of how we go from stimulus to science than Quine achieved.

Causation, Induction and Pecking Pigeons

“There is nothing more basic to thought and language than our sense of similarity; our sorting of things into kinds. The usual general term, whether a common noun or a verb or an adjective, owes its generality to some resemblance among the things referred to. Indeed, learning to use a word depends on a double resemblance: first, a resemblance between the present circumstances and past circumstances in which the word was used, and second, a phonetic resemblance between the present utterance of the word and past utterances of it. And every reasonable expectation depends on resemblance of circumstances, together with our tendency to expect similar causes to have similar effects. (Quine: Natural Kinds pp 116-117)

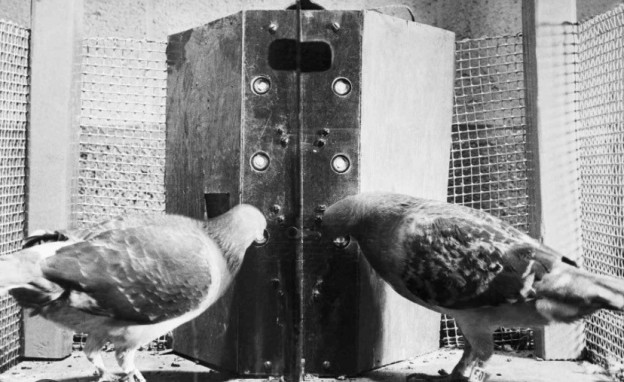

In their 2001 paper ‘Hume’s psychology contemporary learning theory and the problem of knowledge amplification’ Wilson et all’s attempted to update Hume’s epistemology with results from contemporary behavioural science. Hume had famously parsed the laws of association in terms of resemblance, contiguity in space and time, and cause and effect. Wilson et al redescribed Hume’s three criteria using traditional behavioural science. So, for example, they explained resemblance in terms of stimulus generalization. Stimulus generalization is where an organism under stimulus control also responds to stimulus that bears a formal resemblance to the stimulus. And they gave an example of a Pigeon trained to peck under the stimulus of a red light and how scientists could establish a curve in the Pigeons behaviour by altering the stimulus (fading from a red light to a yellow light). Quine had made a similar argument to this in his The Roots of Reference.

“Reception is flagrantly physical. But perception also, for all its mentalistic overtones, is accessible to behavioural criteria. It shows itself in the conditioning of responses. Thus suppose we provide an animal with a screen to look at and a lever to press. He finds that the pressed lever brings a pellet of food when the screen shows a circular stripe, and it brings a shock when the screen shows merely four spots spaced in a semicircular arc. Now we present him with those same four spots, arranged as before, but supplemented with three more to suggest the complementary semicircle. If the animal presses the lever, he may be said to have perceived the circular Gestalt rather than the component spots.” (The Roots of Reference p. 4)

One key difference between Quine’s argument and Wilson et al is that Quine used the behavioural evidence to speculate on the perceptual experience of the organism while Wilson et al eschewed this speculation. This is in keeping with differences in the philosophy of Quine and those of a Contextual Behavioural Science approach. Despite some passages which indicate otherwise; Quine is mechanist whose priority is in explaining behaviour in terms of physiological mechanisms. This mechanistic philosophy puts him at odds with the pragmatism of contextual behavioural science.

For both Quine and the Contextual Behavioural Scientist stimulus generalization will count as a behavioural criterion for resemblance. When it comes to contiguity in space and time the Contextualist Behavioural Scientist speaks instead of contingencies. So, they are not concerned merely with close temporal paring, rather they are interested in “the relative likelihood of one event given the other, and that same event given the lack of the other” (Wilson et al. p.9). They do note that contiguity will predict a contingency, and for most purposes stimuli which are nearby in time will be most psychologically salient (ibid p. 9). A 0.5 second interval between the onset of a conditioned stimulus and the onset of an unconditioned stimulus has been empirically shown to be optimal in for classical conditioning (ibid p.9). If stimuli are separated by time and distance conditioning doesn’t typically occur (ibid p.9).

While Quine uses reinforcement throughout his texts, he doesn’t explicate the type of schedules which are useful for classical or operant conditioning to occur. Some schedules of reinforcement e.g., fixed interval or variable interval schedules indicate the temporal spreads which are most successful in producing conditioning. Such schedules would be relevant to giving a behavioural slant on contiguity in time. But Quine is silent on the issue[1].

Presumably Quine was assuming that reinforcement occurred immediately after the behaviour. But as we know from Skinner’s work different schedules of reinforcement have different conditioning patterns. Quine’s silence on what schedules of reinforcement are involved in acquiring different skills makes it difficult to evaluate his speculations for truth value. Furthermore, unlike the Contextual Behavioural Scientists he has no method of replacing contiguity with contingencies.

Hume’s explains causation by appealing to three principles (1) Contiguity, (2) Succession, (3) Constant Conjunction. He illustrates with his famous billiard ball example. If one billiard ball hits another the other ball moves. This movement involves both balls being contiguous in space and time and one ball hitting the second ball prior to the second ball moving. But Hume notes that in this case all we can say is that one event followed another. To claim that the event caused the other event we need a constant conjunction, e.g., events of type A are constantly followed by events of type B. Wilson et all parse the idea of constant conjunction in terms of similarity “we expect similar effects from similar causes” (ibid p.10).

Wilson et all’s characterisation isn’t quite accurate of Hume’s views. Consider the billiard ball example. Experience looking at billiards shows us that when one ball hits the other ball the second ball tends to move. Hume would parse this as constant conjunction of event of type A preceding event of type B. Whereas Wilson et all would conceive of it as when causes similar to A (one billiard ball hitting the other billiard ball), occur effects similar to B (the second billiard ball moves) occur.

Nonetheless, Wilson et al are correct we cannot explain the constant conjunction of different classes of events without being able to categorize events as similar and dissimilar to each other[2]. And their stimulus generalization is a good behavioural indicator of how once an organisms’ behaviour becomes under stimulus control, we can extrapolate their similarity structures. And how once we switch from looking for contingencies of reinforcement instead of contiguity, we can speak of the probability of one event of kind x following another event of kind y. So, we have a behavioural account of some of the key features of our concept of cause.

Human Specific Capacities

They correctly note that one of the difficulties with the account provided in terms of learning theory is that these learning theoretical tools: stimulus generalization, operant conditioning, classical conditioning etc occur in all mammals. But humans have capacities which go beyond all-other animals. So, they argue we may need new principles to explain uniquely human cognitive capacities. They argue that they can explain this special sauce which only humans possess in terms of Stimulus Equivalence and Relational Frame Theory:

To reiterate, a set of conditional discriminations may be trained wherein the two relations, given A”, pick B” and given A”, pick C” are established by direct reinforcement. In such a case a nonhuman has learned and can respond selectively to precisely these two directly trained relations. A verbally competent human, on the other hand, can respond selectively to trials encompassing A to B relations, B to A relations, A to C relations, C to A relations, B to C relations, and finally C to B relations. From an economic perspective, training two relations to a nonhuman generates two potential relational responses; whereas training two relations to a human generates six (two directly trained, and four derived). (Wilson et al p.13).

After their discussion of human specific capacity in terms of “equivalence of class” they go on to discuss the human specific capacity of “transfer of function”. This capacity has interesting psychological consequences. So, if A1 is paired with an electric shock sufficiently to establish it as an aversive stimulus, then B1 will also work as an aversive stimulus. And if the equivalence relations have been established through multi-exemplar training, then these relations will also be subject to a transfer of function.

“Thus, given A} B training and A}C training, and with C given an aversive function, a human would learn to avoid A, B, and C, whereas a nonverbal organism would require three separate conditioning procedures one for each of the A, B, and C stimuli.” (Ibid p.14)

They also note that while they have spoken of equivalence functions there are also other relational frames such as hierarchy, coordination, oppositeness, greater/smaller than, etc. Another key feature which they note is that these frames are learned through contextual cues (ibid p. 14). The key point is these experimentally derived capacities are unique to humans. Despite hundreds of experiments on dozens of non-human animals Contextual Behavioural Scientists have yet to discover the capacity of any non-human to engage in relational frames. This indicates that there is an innate component to the capacity.

While there is there an incredible amount of behavioural evidence to support the existence of relational frames. And these frames are suggestive for being the secret sauce behind linguistic productivity. There is as of yet very little engagement with generative grammarians to construct mathematical models to see if the types of relational frames discovered can be used to construct the mathematical structures discovered in linguistics. Nonetheless, their experimental studies do take us a long way from Quine’s model of how we acquire our language and theory of the world. Quine vaguely speculated things like similarity quality spaces, and a capacity for analogical synthesis which we use to associate sentences with sentences. But he provided no details on how this was done.

[1] Contiguity in space and time doesn’t always produce conditioning. Wilson et al. discuss the case of taste aversion in rats where through genetic changes the temporal parameters in classical conditioning were modified. This demonstrates that Quine isn’t justified in simply ignoring evidence from schedules of reinforcement when he is speculating.

[2] Quine made a similar point in his postulation of an innate prelinguistic quality space in his Word and Object.