Introduction

In this blogpost I will discuss the relation between Quine and Skinner on the issue of postulating hypothetical neural entities to explain behaviour. I will argue that Quine’s mechanistic position is at odds with Skinner’s radical behaviourism. While Skinner’s position is pragmatic and focuses on whole organism environmental relations; Quine is only interested in how we can use external behaviour as a way of guiding us towards underlying neural mechanisms. I then argue that despite situating himself in the behavioural camp Quine’s views are closer to those of contemporary cognitive scientists.

Having discussed Quine’s relation with Skinner on the above issue I then move on to discuss an analogous debate between contextual behavioural scientists inspired by Skinner and theorists such as Eva Jablonka. This debate indicates that Quine and Skinner’s disagreement is not a mere academic debate from the history of the philosophy of science but is a live debate in contemporary evolutionary theory and behavioural science. The position of Skinner and Contextual Behavioural Scientists is a minority position in the philosophy of science. However, both Skinner and Contextual Behavioural Scientists have come up with concrete empirical results using their minority philosophy of science. It is an open empirical question whether they could have made similar discoveries using standard mechanistic philosophical assumptions.

Quine’s Mechanism

Quine was a philosopher and was primarily interested in issues in logic, epistemology, and ontology. As his philosophical world view grew, his emphasis was on explaining all these subjects naturalistically. Quine wasn’t a psychologist or a linguist. But his naturalism led him to the point where he argued that epistemology was a branch of empirical psychology. So, in working out his epistemology he needed to engage in psychological speculations as well as appeal to empirical data from psychology. Likewise, since Quine recognised the importance of language in our ability to acquire our theory of the world, he needed a theory to explain how we acquired our language. Quine described his position on these matters as behaviouristic. In psychology he argued one may or may not be a behaviourist. But in linguistics one had to be behaviouristic because in acquiring language we relied on intersubjective keying of sounds to objects as we communicated with our socio-linguistic community.

But it is important to note that Quine’s brand of behaviourism was mechanistic. In a sense Quine’s behaviourism was closer to that of earlier behaviourists such as Watson and Pavlov who used behavioural tests to hypothesize about underlying neurological mechanisms. Whereas Skinner and the behaviourist’s who followed him in his radical behaviourist philosophy held a very different view. They were interested in prediction and control of the whole organism in a variety of different contexts. Skinner for example was critical of what he viewed as premature appeal to hypothetical neurological mechanisms by scientists like Watson. He argued that these hypothetical neurological mechanisms were premature given the fact we hadn’t done sufficient behavioural tests to understand behaviour itself.

In fact, Skinner went further than the above he also argued that the behaviourist would become interested in physiology once it could be used as an aid in the prediction and control of whole organisms in their environment. Skinner, unlike Quine, didn’t think that the true or deeper explanation was to be provided at the physiological level. Rather Skinner believed that physiology would eventually be a relevant tool in predicting and controlling the organism when acting in its environment. Physiology would be part of the behavioural stream not its underlying detached cause.

In his paper “Jacques Loeb, B. F Skinner, and the Legacy of Prediction and Control” (1995). Hackenberg analysed how Skinner’s views on prediction and control developed. Hackenberg nicely sums up Skinner’s views on neuroscience below:

“Until physiological events could enter into effective action via the direct prediction and control of behavior, they would remain part of what Skinner (1938) called “the conceptual nervous system” and what Loeb called “the mysticism of the ganglion cells” (Loeb, 1890/1905, p. 114).” (Hackenberg 1995 p.228).

This shows a sharp distinction between Skinner and Quine’s views on this topic. Skinner did argue that physiology would become more important once we got our behavioural facts in order. But he also argued that the behaviourist would become interested in physiology once it could be used as an aid in the prediction and control of whole organisms in their environment. Skinner, unlike Quine, didn’t think that the true or deeper explanation was to be provided at the physiological level. Rather Skinner believed that physiology would eventually be a relevant tool in predicting and controlling the organism when acting in its environment. Physiology would be part of the behavioural stream not its underlying detached cause. Skinner is very clear on his views on this subject:

“When we have achieved a practical control over the organism, theories of behavior lose their point. In representing and managing relevant variables, a conceptual model is useless; we come to grips with behavior itself. When behavior shows order and consistency, we are much less likely to be concerned with physiological or mentalistic causes. (p. 231)”[1]

As can be seen Skinner’s views on physiology are that in so far as it is a useful tool in the prediction and control of the organism, we can appeal to it. But he is less interested in postulating neurological mechanisms to explain the behaviour of organisms. Quine’s views on this topic are very different than Skinners. One of the primary reasons for this divergence is that Quine is interested in explanation of behaviour not just prediction and control.

Quine on Hypothetical Entities

Throughout his career Quine has been censorious in relation to superfluous appeals to hypothetical entities. Thus, Quine has criticized appeals to meanings, ideas, and propositions to explain linguistic behaviour. His reason for criticizing these notions is that he thinks that they are shadowy notions which distract us from looking at actual behaviour in concrete circumstances. But Quine has shown less misgivings about hypothetical structures when it comes to postulating neurological structures as an explanation of behaviour. Quine has specified on numerous occasions that the thinks that the deeper level of explanations are to be found at the neurological level not at the behavioural level.

Quine is explicit about this when it comes to the notion of a disposition. When an organism has a disposition to engage in certain behaviours in certain circumstances Quine thinks we should aim to cash out these dispositions neurologically eventually. In the meantime, we should think of dispositions as hypothetical neurological states:[2]

“Each disposition, in my view, is a physical state or mechanism… Where the general dispositional idiom has its use is as follows. By means of it we can refer to a hypothetical state or mechanism that we do not yet understand, or to any of various such states or mechanisms, while merely specifying one of its characteristic effects, such as dissolution upon immersion in water.” (ibid p.10)

Quine’s use of the dispositional idiom set him and Chomsky at odds. Quine had defined language as a “complex of dispositions to verbal behaviour” . Chomsky rejected this definition because he argued that disposition used in the above sense meant that we could specify the probability of a word being used in a certain circumstance. And Chomsky argued that it is senseless to speak of the probability of a word being spoken on a random occasion. Quine argued that he was speaking of the probability of a word being spoken in a particular circumstance of query and assent. Language is an incredibly complex phenomenon. We still don’t have a clear understanding of the probability of a sentence being spoken in concrete circumstances. So, it may help us understand the notion of disposition in terms of a simpler organism in a tightly controlled experimental setting.

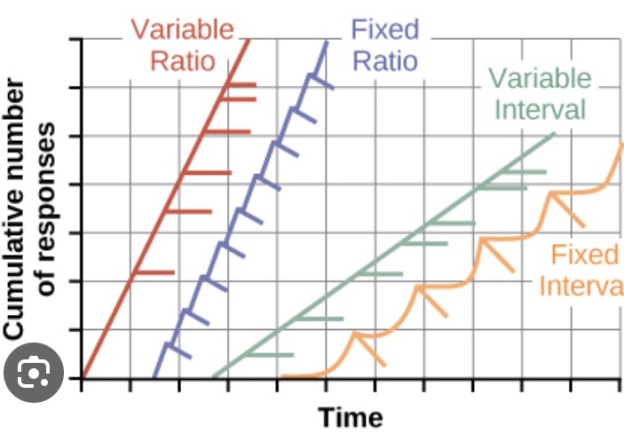

If we take a Pigeon in a Skinner box who has the box tailor made to his size and who is typically operating at 80% of its ad lib weight (Fester and Skinner p. 29). And we put it on a fixed interval ratio schedule of reinforcement for pecking at lights of a particular hue. We will end up with curve which is predictive of the Pigeons behaviour under this schedule of reinforcement. This can be cashed out in the dispositional terms; Pigeon W in a state of deprivation X has a disposition to peck in way Y under schedule of reinforcement Z[3]. Here we have a real behavioural regularity (albeit in an artificially contrived environment), and it is instructive to think about how Quine would handle this case.

When discussing solubility of salt in water Quine argued that this disposition of salt to be soluble in water ultimately needs to be cashed out in terms of underlying physical structures for us have a proper explanation of it. Quine would presumably make the same argument when it comes to Pigeon’s pecking behaviour under a schedule of reinforcement. Skinner’s difficulty with jumping straight to physiological mechanisms was that it was premature and was done prior to us getting our behavioural facts in order. So, for example, when theorists such as Watson were postulating hypothetical neural mechanisms to explain reinforcement they were doing so in ignorance of the distinction between operant and classical conditioning. Furthermore, they were doing so in ignorance of the distinction of various schedules of reinforcement and how they effect behaviour. So, Skinner would have argued that their hypotheses were radically premature, we would be better served by continuing to map out behavioural dispositions under various schedules of reinforcement. Rather than simply postulating a mechanism the instant we discover a regularity.

Skinner does think that we will eventually be capable of advancing our understanding of human behaviour through neuroscience. But he argues that this will be achieved through understanding how the brain physically changes when undergoing schedules of reinforcement not through speculative hypothesis:

“The physiologist of the future will tell us all that can be known about what is happening inside the behaving organism. His account will be an important advance over a behavioural analysis because the latter is necessarily “historical”-that is to say, it is confined to functional relations showing temporal gaps. Something done today which affects the behaviour of the organism tomorrow. No matter how clearly that fact can be established, as step is missing, and we must supply it. He will be able to show how an organism is changed when exposed to contingencies of reinforcement and why the changed organism then behaves in a different way, possibly at a much later date. What he discovers cannot invalidate the laws of a science of behaviour, but it will make the picture of human action more nearly complete. (About Behaviourism pp.236-237)

Skinner’s emphasis on “knowing what is happening inside the behaving organism”, is important. He has no problem with discoveries about the underlying neuroscience which explains the behaviour of the organism in terms of schedules of reinforcement. What he disagrees with is explanations in terms of hypothetical mechanisms.

Skinner argues that appeal to hypothetical entities to explain behaviour amount to what he calls the conceptual nervous system. His criticisms of Pavlov invariably involved chastising him for invoking conceptual analogues for the nervous system which had no neurological reality:

The subtitle of his Conditioned Reflexes is ‘An investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex,’ but no direct observations of the cortex are reported. The data given are quite obviously concerned with the behavior of reasonably intact dogs, and the only nervous system of which he speaks is the conceptual one. (Skinner, 1938, p. 427).

As we mentioned above Quine could be accused of to some degree adopting positions analogous to Pavlov’s conceptual nervous system.

When Quine speaks of hypothetical mechanisms some of his talk would be innocuous from Skinner’s point of view. Thus, when Quine speaks of “…a disposition is a promissory note for an eventual description in mechanical terms” (The Roots of Reference p. 14), there can be little objection. All he is arguing is that dispositional states have underlying physical states. This is an uncontroversial position. But when Quine begins arguing for hypothetical mechanisms to explain perceptual similarity and receptual similarity (ibid p. 18), and claims that postulating such mechanisms is unavoidable (ibid p.24). He is moving into the realm of arguing for a conceptual nervous system. Quine argues that such hypothetical mechanisms are on a par with positing things like genes on hypothetical grounds with the aim being to discover their physical properties later (ibid p. 27).

Despite calling himself a behaviourist, Quine’s discussions of hypothetical mechanisms to explain overt behaviour puts him closer to positions advocated by cognitive scientists (of both a connectionist and computationalist perspective) than it does to behaviourists like Skinner[4]. This dispute between both is largely a philosophical one. It depends on the interests of the researcher. Is the prediction and control of an organism in different contexts the key to a science of behaviour or is giving a mechanistic and reductionistic account of more importance?

In this section we will see how the contemporary disagreement with Jablonka (2018) and Dougher and Hamilton (2018) on the issue of mechanistic postulations mirrors the disagreement between Quine and Skinner. This contemporary debate indicates that the issues between Quine and Skinner are live issues in the philosophy of behavioural science.

In Dougher and Hamilton’s (2018) paper“The Contextual Science of Learning: Integrating Behavioural and Evolution Science Within a Functional Approach”[5] they attempt to integrate Contextual Behavioural Science[6] with Evolutionary science. CBS operates within the Skinnerian pragmatic whole organism philosophy which we discussed above. While scientists in CBS claim to have gone beyond Skinner in many respects empirically, their underlying philosophy is very similar to Skinner’s radical behaviourism.

Dougher and Hamilton integrate evolutionary theory and CBS in the context of learning theory. They focus on research into spatial learning, contrasting mechanistic versus functional accounts of spatial learning. They argue that mechanism was an intellectual ancestor of positivism, the hypothetic-deductive account of science, and methodological behaviourism (ibid p. 16). Following Palmer (1994) they label mechanism an inferred process approach (ibid p. 16). This approach involves using behavioural data to draw inferences about underlying neurological or cognitive mechanisms and appeal to these mechanisms as the causal factors that produce the behaviour. This approach typically involves studying groups of organisms and drawing out statistical facts about these groups to produce mechanistic hypotheses which they hold onto until some prediction fails, or experimental data refutes the hypothesis (ibid p. 16).

Functionalism instead of looking for hypothesised learning mechanisms take the behaviour of the whole organism in relation to its historical and immediate environmental context as the subject matter to be studied (ibid p.16). They look for explanations of behaviour (defined through its antecedents and consequences) in the functional relation between the behaviour and its environmental contexts (ibid p. 16). Because of the heavy emphasis they place on prediction and control they focus their attention on behavioural studies of individuals acting in context. They achieve their generalized results through replication across participants (ibid p. 17). They parse the primary difference between both approaches as follows:

“From the dominant mechanistic perspective, learning is typically defined as changes in an organism resulting from experience…. a functional definition of learning as an ontogenetic adaptation. The emphasis here is not on the organism or its internal mechanisms but on the observed functional regularities between behaviour and environments.” (Ibid p.17)

Spatial Learning

They discuss O Keefe and Nadel’s (1978) work on cognitive mapping theory of the hippocampus[7], and use this as a paradigm example of a mechanistic approach. They don’t argue that O Keefe and Nadel’s work is incorrect, acknowledging that work is still on going on the overall project. However, they point out that Hamilton, Rosenfelt, and Whishaw (2004) have done experimental work on stimulus functions which operate throughout spatial navigation trials (ibid p. 18):

“Results showed that distinct segments of navigation toward a goal location depended on different environmental stimuli, with the initial selection of a direction based on more global features of the environment and subsequent/terminal aspects of the trip based on stimuli located at or near a goal. Thus, fine grain functional relations are operating in spatial navigation.” (Ibid p. 18).

They argue even if one is a mechanist, one should be on the lookout for functional relations before automatically appealing to inferred entities.

Dougherty and Hamilton’s paper was published in Sloan-Wilson and Hayes (eds) Evolution and Conceptual Behavioural Science. And at the end of their chapter in a section called “Dialogue on Learning”, they a discussion with one of the other authors in the book Eva Jablonka. In Eva Jablonka’s paper “Classical and Operant Conditioning: Evolutionarily Distinct Strategies?” (co-authored with Bronfman and Ginsburg) she discussed evolutionary origins of operant and classical conditioning arguing that we couldn’t definitively argue that they were separate mechanisms. She argued that both operant and classical conditioning are intertwined and can be explained with a mechanism called limited association which evolved during the Cambrian Explosion and may have been responsible for the unprecedented diversity of species at that time.

When commenting on Jablonka’s paper Dougherty and Hamilton argued that the postulation of a mechanism of limited associative learning was unnecessary and instead, we should be looking for “a difference in the kind or environmental regularities that can influence behaviour” (Dialogue on Learning p. 50).

When Jablonka pointed out that we need something in different kinds of organisms to explain how they interpreted the world. They replied when you start to identify different parts of the brain in terms of functions, you lose sight of environmental-behaviour relations (ibid p52). At this point in the discussion Steven Hayes who is the founder and lead figure in Contextual Behavioural Science discussed the concept of taste aversion in rats an argued that most experts in the field explain this as a kind of temporal distortion of classical conditioning. And Hayes notes the following:

“I would be surprised, Mike, if you think it was a bad thing to look at the underlying neurobiology of taste aversion, given this extraordinary distortion of temporal parameters.” (ibid p. 53)

The reply that Hayes gets makes it clear that the contextual behavioural scientists are only interested in the neurobiology of taste aversion to the extent that it gives prediction and control of the organism in particular contexts. It is unclear whether what precisely their views on neurological mechanisms in the brain is other than the fact they are only interested in such postulations to the extent to which they help us predict and control the organism and his environment.

One can see from the above discussion that the debate as to whether it is advisable to postulate hypothetical mechanisms to explain the behaviour of organisms is still a live issue and isn’t limited to disagreements on the philosophy of science fifty years ago. It is fair to say that the position adopted by Quine and Jablonka would still be the mainstream position adopted by the scientific community. And those working in the radical behaviourist or CBS positions are in the minority. But obviously a philosophical disagreement cannot be decided by majority rules. And the methodology adopted by CBS while not mainstream hasn’t stopped them achieving notable success achieving experimental understanding in relation to rule-following, stimulus equivalence and relations of coordination etc. It is an open empirical question as to whether they could have achieved these results adapting a more mechanistic philosophical framework.

[1] B.F. Skinner: A case history in the scientific method 1956.

[2] Quine is speaking of any physical entities disposition e.g., the disposition of salt to dissolve when in water. He thinks these can be cashed out in terms of some hypothetical physical states. Here we will limit our attention to dispositions of living organisms to behave in certain ways in certain circumstances.

[3] Skinner obviously wouldn’t parse the Pigeons behaviour in the above manner.

[4] Though Quine’s positions do bear some similarities to pre-Skinnerian behaviourists such as Pavlov and Hull.

[5] This paper was printed in Wilson and Hayes (eds), ‘Evolution and Contextual Behavioural Science’

[6] Henceforth Contextual Behavioural Science will be referred to as CBS.

[7] O Keefe’s work on place cell’s role in the cognitive maps won him the Nobel Prize in (2014).